Impossible Worlds and Temporalities in Haruki Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore: Readers’ Paradoxical De

- CHANG Yu Ting

- Jun 15, 2016

- 12 min read

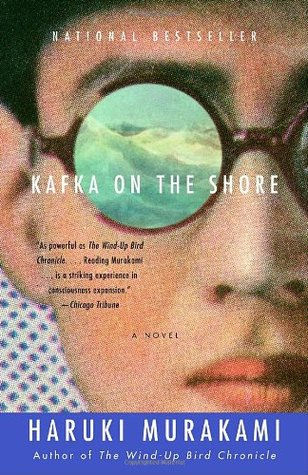

The act of reading is dependent on the text’s comprehensibility but also mutually the readers’ ability to make sense of the text. Traditionally, a satisfying reading experience is defined largely by the author’s success in creating a sense of immersion and relatability in the readers, and often to achieve this, the work must entail a certain degree of logicality and comprehensibility. It needs to provide a logical frame for the readers to guide their way through the story. The novel Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami breaks some of these traditional notions of reading through experimentation with readers’ expectations and reception by constructing illogical and impossible worlds. Compared to some of the other more mainstream and realist works by Murakami like Norwegian Wood, Kafka on the Shore is “very complicated and very hard to follow” (Paris Review) as Murakami expressed in an interview. It is however a “strategic choice” (Paris Review), according to Murakami, to publish a more mainstream work first in order to build a readership, so that once readers are captivated, they will continue to read other works of his despite the differences in style.

The notions of impossible worlds and temporalities are especially significant and helpful in understanding Murakami’s more surrealistic and postmodern text Kafka on the Shore. Impossible worlds are “full of paradoxes” (Ryan 368) and embedded with logical contradictions. They are “so thoroughly infused with ontological instability that readers cannot tell what exists and what does not” (Ryan 370). These impossible worlds are also not bound by fundamental human beliefs about time, rejecting the traditional idea that there is a “fixed directionality in time” and suggesting that this “can be broken by reversing its flow” (Ryan 373). This paper puts forward the argument that Murakami experiments with readers’ expectations and extends their acceptance of these impossible worlds and temporalities in Kafka on the Shore through paradoxically keeping them both immersed and detached. Its metaphysical, illogical plot and temporal elements might elicit confusion and a difficulty to relate, thus creating a sense of disengagement in readers. Hence, Murakami ensures to maintain a certain degree of understandability in his novel through utilizing different strategies such as building in implicit connections between the two different “parts”, inserting self-reflexive comments and subtle language guidance to sustain readers’ interests and immersion.

To facilitate discussion, it is vital to elucidate this paradoxical yet circular movement between immersion and detachment. Reader’s immersion can refer to their entry into a fictional world, and this is often accomplished partially through some degree of identification with the characters. Focalization is commonly utilized to achieve this kind of empathetic identification. This ability to relate often aids increased comprehension and heightened understandability, and in return enhancing that sense of immersion into the fictional world. Detachment, on the other hand, can be characterized as a feeling of separation and alienation as elicited by unfamiliarity. Readers often find a lack of graspable human concepts. There is little logicality, causality or even correlation in that unfamiliar setting. This difficulty in comprehension often discomforts and leads to feelings of disengagement, and possibly even a loss of interest to read on. I will first explore how Murakami creates this sense of detachment and immersion through the alternating narrative structure of the novel. The idea of hermeneutic circle will also be helpful in informing the discussion as it bears some resemblance to the circular, back-and-forth movement between immersion and detachment. I will then focus on the techniques utilized by Murakami to aid readers’ immersion. I will also explore the idea of impossible temporalities in the novel and how it affects readers’ sense of detachment and immersion. I will then examine how Nakata stands as a symbolic figure that represents the notion of timelessness and mirrors readers’ inability to assimilate the different moments and “parts” into a “whole”.

In Kafka on the Shore, the sense of detachment elicited in readers is produced through and facilitated by the unorthodox narrative structure of the novel. The novel consists of two technically separate plotlines that delineate the stories of Kafka and Nakata, who do not come into direct contact but whose fates converge in implicit ways. The odd numbered chapters tell the story of Kafka, and the even numbered chapters are about Nakata. The alternating chapters potentially create this sense of disorientation as readers are forced to switch between the two plotlines. For example, the last sentence that concludes Kafka’s part in chapter 3 says, “I shut my book and look for a while at the passing scenery. But very soon, before I realize it, I fall asleep myself.” (Murakami 26) The beginning of the next chapter then abruptly switches to an interview with a doctor who has knowledge of Nakata’s childhood accident. The form and tone alters drastically:

“U.S. ARMY INTELLIGENCE SECTION (MIS) REPORT Dated: May 12, 1946

Title: Report on the Rice Bowl Hill Incident, 1944

Document Number: PTYX-722-8936745-42216-WWN

The following is a taped interview with Doctor Juichi Nakazawa (53), who ran an internal medicine clinic in [name deleted] Town at the time of the incident.” (Murakami 27)

The novel is structured in a way to prevent complete immersion as readers are constantly brought in and out of the two different stories. This back and forth, in-and-out movement between immersion and detachment has interesting parallels to the working of a hermeneutic circle. “It is a circular relationship” (Gadamer 291) in the way that readers form expectations from reading certain parts or sentences, then utilizing that assumption to determine and imagine the whole. These expectations however continue to change and modify themselves as readers are exposed to more parts of the story. Thus, “the movement of understanding is constantly from the whole to the part and back to the whole” (Gadamer 291). All processes of reading, to some extent, involve this circular hermeneutic movement. Kafka on the Shore is however unique in the way that Murakami prompts synergetic reattachment between the paradoxical oscillation of immersion and detachment between the whole and the part. Kafka and Nakata’s stories can be considered as two “wholes” but also two “parts” that come together to form a “whole”. Readers can choose to read either plotline as a separate story and it would still make sense as a “whole”. However, if considering the two plotlines as “parts”, readers will have to detach themselves and move away from Kafka’s plotline in order to read and immerse in Nakata’s story or vice versa. Interestingly, when readers move onto reading one of the other plotlines, they will find linkages and details that are relevant and connected to the previous parts. For example, only through reading both plotlines, do readers discover that the cat killer Johnnie Walker in Nakata’s story is actually Kafka’s father. This sudden, uncanny connection to the other plotline might momentarily detach readers as they are reminded of the other “part”. However at the same time, readers are prompted to bring in their knowledge from the other “part” and connect these pieces to paint a clearer picture of the “whole”. They are momentarily “brought out” of the story so as to “bring in” the other part. This creates a moment of synergetic reattachment between the “parts” as readers are empowered to produce new meanings for themselves through making associations and connections. This is precisely what characterizes Murakami’s experimentation - he pushes the bounds of readers’ acceptance with the novel’s seeming incoherence and difficulty for narrative integration, but he also implicitly ties the novel together through these moments of connection and reattachment to maintain readers’ interest and immersion.

Murakami also ensures to sustain readers’ interest and immersion in the story through various other techniques. One of the most frequently employed methods is to insert self-reflexive comments that reflect the inherent strangeness of the story. When Johnnie Walker describes his plan of collecting the souls of cats to create a flute, Nakata “ha[s] no idea” (Murakami 149) what he is talking about and questions, “A flute? Was he talking about a flute you held sideways? ... And what did he mean by cats' souls? All of this exceeded his limited powers of comprehension. But Nakata did understand one thing: he had to locate Goma and get her out of here” (Murakami 149). Similarly confused, readers are able to identify with Nakata’s thoughts and feelings as Walker’s plan challenges not just the character’s ability to comprehend but even the readers’ “powers of comprehension”. The comment also aids readers in situating themselves in Nakata’s role by positioning him as the focalizer as events are narrated through his perspective. These self-reflexive comments create an interestingly paradoxical dual effect. On the one hand, they are designed to help readers with comprehension and immersion in the story, but on the other hand, the self-reflexivity also generates the feeling that the character is “jumping” out of the story to directly address the reader and breaks the fictional distance. This ironically detaches readers from the fictional world and reminds them of the story’s artificiality and peculiarity. Another subtle technique to move forward the seemingly illogical plot is to insert “guiding” phrases like “Nakata did understand one thing”, which implicitly hints to readers that as long as they can comprehend this one piece of information, they can still carry on with reading. It provides readers with something that they can grasp amidst the confusion.

Murakami also plays with the human conception of temporality through subverting the “arrow of time” – a belief in the fixed directionality of time. He utilizes the figure of Nakata and Kafka to symbolically redefine and create a metaphysical space of timelessness that transcends the socially constructed notion of human time. This radical and subversive play with temporality forces readers out of their “comfort zone” – they can no longer apply the existing human conception of empirical time in comprehending this fictional world, eliciting feelings of discomfort and detachment. Taking Kafka as an example, he suspects he has murdered his father through a dream that transgresses spatial and temporal possibilities:

"But maybe I did kill my father with my own hands, not metaphorically. I really get the feeling that I did. Like you said, I was in Takamatsu that day--I definitely didn't go to Tokyo. But in dreams begin responsibilities, right?"

Oshima nods. "Yeats."

"So maybe I murdered him through a dream," I say. "Maybe I went through some special dream circuit or something and killed him." (Murakami 214)

The notion of empirical time can no longer be applied in understanding Kafka’s case. The possibility of a person being in two places at the same time exists and does not defy logic in Kafka’s world. Readers are led into a dream-like fictional world here instead – a “textual universe with characteristics of dream” where objects undergo “incessant metamorphoses” and there is a “general lack of ontological stability” (Ryan 377). To enter Kafka’s world, readers must accept these seemingly contradictory and impossible temporalities “as an integral part of the fictional world” (Ryan 377). Scholar Matthew Strecher comments that Murakami’s “metaphysical other world stands outside the boundaries of what we think of as reality, can (usually) be reached only unconsciously, by accident or chance (much, in fact, like entering the state of sleep)” (71). This creates a sense of detachment from reality as the notion of time defies normal logic, especially if readers find it difficult to suspend their disbelief. The way time exists in Murakami’s fictional world “run[s] unpredictably, in all directions, quite unlike the linear, mono-directional tool we have constructed in the conscious, physical world” (Strecher 71-72). It is precisely this discrepancy in notions of time between real life and Murakami’s metaphysical world that discomforts readers and arouses feelings of disengagement as it challenges and defies our preconceived ideas about time. The non-linear temporality breaks the conventions of realist fictions in which narrative coherence is expected, and instead challenges readers to actively assimilate and integrate the different scattered moments into a comprehensible, unified “whole”.

Nakata is a symbolical figure that represents the timelessness in the metaphysical fictional world Murakami constructs. Nakata suffers from an inability to read and write after a childhood accident, and this intellectual impairment profoundly prevents him from taking in complex information. He cannot adequately assimilate the past with his present as he could only remember the most basic and simplest details, nor can he make complex future projections due to his mental incapability. Nakata is thus a symbolical figure that lives infinitely in the present – he is, and can only be concerned with the most immediate present happenings most of the time. It is almost as if “time does not ‘pass’—does not move—in th[is] other world” for Nakata (Strecher 72). Kafka is an interesting temporal figure that parallels Nakata’s condition. He runs away from home to escape from a past prophecy his father cast on him, but at the same time, he does not know where to run and there is no definite destination. Kafka is in a way, figuratively, escaping from the past, yet he also has no sense of the future. He simply goes with the flow and lives in the moment, accepting whatever he encounters on his runaway journey. Kafka resembles Nakata in the way that both of them are stuck in the present and this doubled symbolic temporal figure further reinforces the notion of a metaphysical timelessness.

However, as Strecher argues, this does not mean “no form of time exists” in this metaphysical fictional world. Instead, the world is “bound up in a transcendent form of ‘Time’ (with a capital T)” that “exists in the ‘other world’ as a totality, a unity that precludes any distinction between past and future, functioning solely as an endless ‘present’” (Strecher 72). This elimination of distinction between the past and future precisely challenges that notion of fixed directionality in human time. Time does not flow from the past to the future or vice versa, but they are all encompassed in a unity in the metaphysical world. At one point, Nakata contemplates his condition:

"It's not just that I'm dumb. Nakata's empty inside. I finally understand that. Nakata's like a library without a single book. It wasn't always like that. I used to have books inside me. For a long time I couldn't remember, but now I can. I used to be normal, just like everybody else. But something happened and I ended up like a container with nothing inside." (Murakami 318)

Utilizing this metaphor of the library, Nakata expresses this hollowness he suffers from as he is unable to take in information and “store books” in him. He is infinitely stuck in the present as he experiences a very different and totalizing notion of temporality in the metaphysical world compared to readers. Strecher argues that this creates “the illusion of timelessness in the metaphysical realm, and those who enter it can never gain their temporal bearings” (72). The sense of detachment in readers is therefore even further intensified because it is potentially difficult to grasp that intangible emptiness and timelessness Nakata is experiencing. Readers are undeniably temporal beings living in a material world and reading itself is a fundamentally temporal activity as well. This increases their difficulty to relate to the metaphysical temporality and realm that is being constructed and depicted in Kafka on the Shore. Here, Nakata stands as a symbolic figure that reflexively represents readers’ difficulty or even inability to integrate the different moments of their reading experience into a coherent “whole”. This difficulty might then challenge readers to seek alternative ways to assimilate these “parts” into a “whole”. One possible alternative is to look at the “gaps” between the different parts. By paying attention to the possible links that are absent on the surface, readers might discover new potentialities for integration through this mode of deep reading. To achieve this, readers will have to detach themselves from the surface of the text. However, this condition could not be generalized to every single reader. For if readers are able to overcome this difficulty and can assimilate their reading experiences with the notion of timelessness, they might experience feelings of immersion instead of detachment. They have entered and immersed themselves into a new realm of time, and this detachment from reality paradoxically and ironically reinforces and strengthens their immersion in the metaphysical fictional world instead.

To conclude, through paradoxically keeping readers both detached from and immersed in the story, Murakami is able to experiment and play with some of the conventional expectations readers possess when they read. Murakami also attempts to enhance readers’ acceptance for worlds that seem impossible and illogical. Having alternate chapters already structurally changes the reading experience as it requires a constant back-and-forth immersion and detachment oscillation in order to construct a “whole” through its “parts”. It asks readers to become active engagers as they detach themselves to bring in knowledge from other “parts” and reattach new meanings to and between them. Murakami also ensures readers some degree of comprehension and immersion through inserting self-reflexive moments and guiding language. Then Murakami challenges notions of human time by introducing alternative representations of temporality in the metaphysical realm. The failure to assimilate the temporality in the fictional world might result in feelings of detachment, but successful readers will find themselves immersed in a new realm of timelessness. This act of catering for his readers however conjures to mind a more profound literary dilemma – is there an experimental limit to pushing readers’ acceptance of the impossible? As Hans-Georg Gadamer comments, “when we read a text we always assume its completeness”, and “a unity of meaning” equates it as “intelligible” (294). Murakami’s experimentation is significant precisely because of his attempt to challenge this notion of unity and completeness in the traditional reading experience. His novel endeavours to extend readers’ acceptance for impossibilities and narrative incoherence while also empowering and trusting them with the ability to synthesize the material through the paradoxical oscillation between immersion and detachment, surface and depth, “parts” and “wholes”. Reading and writing is a two-way relationship, and Murakami heavily stresses the role of the reader through this experimentation. Can we really revolutionize the current conventional mode of reading that advocates unity and comprehensibility and instead experiment with narrations of disorientation, disjunction, ambiguities, incompleteness and contradiction?

Works Cited:

Gadamer, Hans-Georg, and Joel Weinsheimer. Truth and Method. New York: Continuum, 1994.

"Haruki Murakami, The Art of Fiction No. 182." Review. Paris Review 2004: Web. <http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/2/the-art-of-fiction-no-182-haruki-murakami>.

Murakami, Haruki. Kafka on the Shore. London: Vintage, 2005. Print.

Ryan, Marie-Laure. "Impossible Worlds." The Routledge Companion to Experimental Literature. By Joe Bray, Alison Gibbons, and Brian McHale. London: Routledge, 2012. 368-79. Print.

Strecher, Matthew. "Into the Mad, Metaphysical Realm." The Forbidden Worlds of Haruki Murakami. U of Minnesota, 2014. 69-119.

Comments